How Did Oppenheimer's Special Effects Team Recreate an Atomic Blast Without CGI?

No, it did not involve setting off an actual nuclear device.

Christopher Nolan raised many an eyebrow in late 2022 when he revealed that his upcoming World War II biopic — Oppenheimer (opening on the big screen July 21) — had achieved the effect of a detonating atomic bomb without the use of CG.

This led many fans to jokingly speculate that the pioneering filmmaker with an eye toward stark realism had somehow convinced Universal Pictures to purchase and blow up an actual nuclear device in the middle of the desert. Thankfully, this wasn't the case.

In an interview with Total Film for the magazine's June 2023 issue (now on sale), Special Effects Supervisor Scott R. Fisher peeled back the curtain on his sixth team-up with Nolan. Given the film's grounded material, the special effects team enjoyed a much lighter workload when compared to the larger-than-life visuals they were asked to create for previous outings like Interstellar and Tenet.

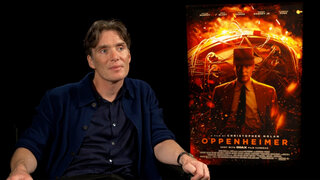

RELATED: Oppenheimer Star Cillian Murphy On Working With Christopher Nolan 6 Times: 'It Feels Absurd'

"It was definitely not as rigorous with day-to-day filming," said Fisher. "[Nolan] said, 'There's not as much stuff for you on this as the other one, but there's a couple of things we do have to cover. And that was, of course, the Trinity explosion, and some prop builds, and elements of different things that we had throughout the film."

"I find CG rarely is able to grab you," Nolan told Empire for the magazine's issue (now on sale). "It tends to feel safe. Even if it's impressive and beautiful, it's difficult to make you feel danger. And we were presenting the ultimate danger. We needed it to feel threatening, nasty and frightening to the audience."

For the Trinity Test (the world's first-ever atomic explosion), Fisher and his team used one of the oldest tricks in the Hollywood playbook: forced perspective. "We don't call them miniatures; we call them 'big-atures,'" he explained. "We do them as big as we possibly can, but we do reduce the scale so it's manageable. It's getting it closer to the camera, and doing it as big as you can in the environment."

As for the pyrotechnic side of things, the intense blaze was "mostly" a combination of gasoline and propane "because you get so much bang for your buck," Fisher said (we're gonna assume the pun was very much intended). Aluminum powder and magnesium were then added to the conflagration in order to approximate the instant blinding flash that accompanies a nuclear blast. "We really wanted everyone to talk about that flash, that brightness. So we tried to replicate that as much as we could."

In his aforementioned chat with Empire, Nolan described the techniques as "very experimental" and ranging from large to miniscule. "Some on a giant scale using explosives and magnesium flares and big, black powder explosions of petrol, whatever," he said. "And them some absolutely tiny, using interactions of different particles, different oils, different liquids."

Simulating the flash and mushroom cloud was simply an appetizer for the true challenge: visualizing the fiery abstractness within Oppenheimer's brilliant mind — "his ability to look into matter, and see and feel the energy there," Nolan said. We'd expect nothing less from a man whose desire to give the world an accurate depiction of a black hole yielded a real-world scientific study.

"The most obvious thing to do would be to do them all with computer graphics," the writer-director concluded. "But I knew that that was not going to achieve the sort of tactile, ragged, real nature of what I wanted ... The goal was to have everything that appears in the film to be photographed. And have the computer used for what it's best for, which is compositing, and putting ideas together; taking out things you don't want; putting layers of things together."

Oppenheimer arrives exclusively in theaters Friday, July 21.

Jonesing for another thriller based on true events? A Friend of the Family is now streaming on Peacock.