Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive show news, updates, and more!

The Origin Story Behind Every Mascot in Olympics History (PHOTOS)

From Waldi the Dachshund to the Phryges of France, a look at the often adorable and sometimes puzzling mascots of the Summer and Winter Games.

A pair of animated hats are getting as much face time in the promotion of the 2024 Paris Games as the likes of Simone Biles, LeBron James, and Katie Ledecky.

That’s because the Phryges, the latest in a half century tradition of official mascots for each Summer and Winter Olympics, have an important role in helping this year’s host city promote both the Games and itself to an international audience.

“Mascots for their Olympic hosts are symbolic, typically with heartfelt connection to the region and its people,” T. Bettina Cornwell, professor of marketing at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business, told NBC Insider.

“For marketing at the international level, mascots are a visual touchpoint for use in promotion. From a ground level marketing standpoint, mascots are the quintessential keepsake representing the Games.”

Here’s a look at Olympic mascots through history.

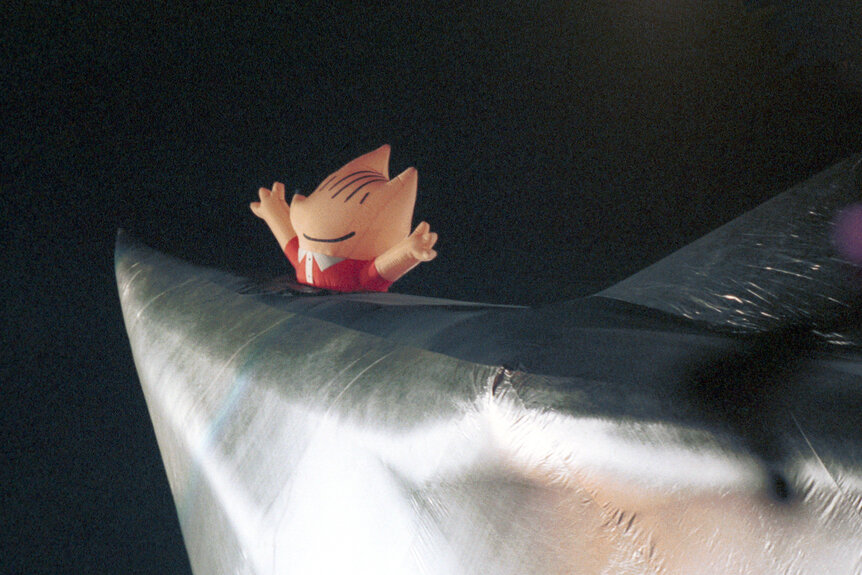

The Phryges, Paris 2024

The latest in the line of adorable avatars representing the Olympic Games and the cities that host them are the Phryges (pronounced free-jee-us, according to organizers) of this summer’s Paris Olympics. This “tribe” of anthropomorphic hats are based on caps worn during the French Revolution as a symbol of liberty and have a deep significance in the culture of the country. Dressed in the French national colors of red, blue, and white, the Phryges feature eyes that taper into ribbon cockades, another national cultural staple.

RELATED: Sha’Carri Richardson's Reaction To Meeting Snoop Dogg Is So Relatable (VIDEO)

Though there are many Phryges used in marketing animation for the Games, there are two main characters, one each representing the 2024 Paris Olympics and the other symbolizes the 2024 Paris Paralympics, with a prosthetic leg.

It’s early to tell if those designs will stand the test of time and be remembered among the best of the Olympic mascots, but the early returns are that they check several boxes.

“The Phrygian hats of Paris 2024 work on two levels,” said Cornwall. “For children, and the light-hearted, they are clearly happy and playful as is typical of Olympic mascots, but at a deeper level they represent the ideals of the French people.”

Bing Dwen Dwen, Beijing 2022

For Beijing’s second stint as an Olympic host, the organizing committee opted for a more streamlined strategy than the five mascots of the 2008 Summer Games. That said, Bing Dwen Dwen, a panda in an astronaut suit made of ice, proved memorable in his own right.

“We could've used elk or rabbits, but there was no doubt that a panda was the best choice because it immediately triggers thoughts about China at first glance for everyone across the world," designer Cao Xue told the Haizhu newspaper at the time.

The name was a combination of Bing, or “ice,” and Dwen Dwen, a term of endearment for children, the target audience of the mascot. It’s high-tech shell was designed as a nod to the Chinese prioritization on technology and space travel in the 21st Century.

Miraitowa, Tokyo 2020

Artist Ryo Taniguchi opted for a child-friendly look that combined modern technology and Japanese cultural staples like samurai helmets and cherry blossoms for the mascot designs that topped the nationwide competition for the 2020 Tokyo Games. His big-eyed, super-powered characters would fit right in a television anime. That cutesy superhero aesthetic ultimately were chosen in a vote by an estimated 6.5 million Japanese school children.

But Taniguchi also designed the Olympic and Paralympic mascots to have appeal outside his country: “"I integrate Japanese nature, tradition and the country's future,” the artist told Kyodo News. “It's the selling point. So it's not just Japanese but has those elements.

RELATED: Are Olympic Medals Real Gold? The Answer May Surprise You

Miraitowa, the Olympic mascot, takes his name from a combination of the Japanese words for “future” and “eternity,” meant to project an eternal optimism for the world to come. Someity, the Paralympic mascot, is named after a type of cherry blossom that inspired her image, but also is meant to phonetically evoke the English words, “so mighty.”

Soohorang, PyeongChang 2018

After the success of Hodori, the tiger mascot of the Seoul Summer Games 20 years earlier, organizers of the PyeongChang games opted for a sequel of sorts. Soohorang, the 2018 Winter Olympics mascot was a stylized white tiger, a symbolic guardian totem in Korean culture.

The name came from a combination of the Korean word for “protection” and the middle letter in the word for “tiger.” While tigers have a special place in Korean folklore, ones with white fur are considered especially important, as their coloring was a sign that they had reached true understanding about the meaning of life.

An Asiatic black bear named Bandabi represented the Paralympic Games.

Vinicius, Rio 2016

Rather than selecting one type of local animal to represent the Rio Games, organizers opted to spotlight just about all of them. Vinicius, designed by Birdo Productions to be equal parts bird, monkey, cat, and video game character, is named after Vinicius de Moraes, the famed Brazilian poet and musician who penned the hit song, “The Girl From Ipanema.”

The Paralympic mascot entry was named Tom, and designed as a walking mixture of Brazilian flora that boasted a leafy head.

The Hare, the Polar Bear, and the Leopard, Sochi 2014

A nationwide contest that culminated in a 2011 televised finale produced three Russian mascots for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi: A hare, a polar bear, and a leopard, designed by Silviya Petrova, Oleg Seredechniy, and Vadim Pak, respectively. None of the animal mascots were ultimately named, a rarity in Olympic mascot history, but each represented the wildlife of the region. The trio were popular enough in Russia to be minted on the 25-ruble coin.

There were actually more than three mascots representing Sochi that year: A ray of light and a snowflake were selected by a panel of Paralympic athletes to represent the Paralympic Games.

Wenlock, London 2012

For the 2012 Summer Games, London deviated from the usual sources of mascots – local fauna and local legends. Instead, the designers at the Iris Design Agency developed Wenlock and Mandeville, a pair of cyclopean beings with a look more extraterrestrial than English.

Reaction was mixed, to borrow the British penchant for understatement. Harrison Mooney, a columnist for the Vancouver Sun, wrote: “These phallic bugbears fitted out in foppish puffery are by far the worst mascots of any Olympics, and I say this while trying to suppress my memories of Atlanta's amorphous blob Whatizit.”

RELATED: Watch Snoop Dogg’s Hilarious Commentary on the Steeplechase at U.S. Track & Field Trials

The name Wenlock, the mascot for the Olympics, comes from the town of Much Wenlock in Shropshire, about 150 miles away from London, which is the birthplace of William Penny Brook, a key figure in the revival of the Olympic Games in the late 19th Century. Mandeville, the character representing the Paralympics took the name of the town of Stoke Mandeville, site of the original Paralympic Games.

A backstory was created by Michael Morpurgo, a beloved British children’s literature author, which explained that Wenlock and Mandeville were the last two drops from a steel beam used in the making of Olympic Stadium in London which were then brought to life by a rainbow.

Quatchi and Miga, Vancouver 2010

Organizers of the Vancouver Winter Games leaned heavily into native cultures of the region as inspiration for the 2010 mascots. The result, designed by Michael Murphy and Vicki Wong, were three mythical animals drawn from aboriginal legends from in and around British Columbia.

Miga, a mythical sea creature that’s part killer whale and part bear, and Quatchi, a sasquatch, were the Olympic mascots, while Sumi, an animal guardian spirit of the mountains, was the Paralympic mascot.

The Vancouver editions would end up as some of the most memorable mascots in Olympic history. “The sasquatch delivered a bit of squeezable mythical character and the little walking killer whale a bit of whimsey,” Cornwall said. “They were approachable and, in a word, sweet.”

The connection to indigenous culture also extended to the choice for the official symbol of the Games – a version of an Inukshuk, a stone landmark used by the Inuit people of the Arctic.

Beibei, Jingjing, Huanhuan, Yingying, Nini, Beijing 2008

The Beijing Summer Games were so epic – as the mammoth opening ceremonies would prove -- that they required a record five mascots. Each of the five represented one of the natural elements: Beibei the blue fish is an avatar of water, Jingling the black panda symbolizes the forest; Huanhuan the red child is an embodiment of fire; Yingying the yellow antelope represents the earth; and Nini the green swallow represents the sky. Together they also match the colors of the Olympic rings.

Designed by legendary Chinese artist Han Meilin, the kid-friendly mascots were also called “the Fuwa dolls,” which translates into English as “the good luck dolls.”

The five mascots were not the first contribution Meilin made to the Olympics: He designed the “Five-Dragon Clock Tower” that was erected in the Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park for the 1996 Summer Games.

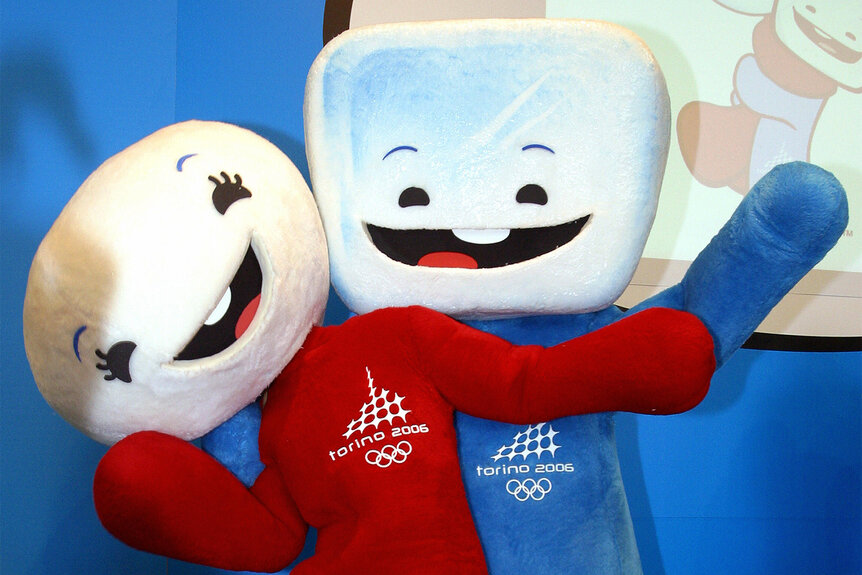

Neve and Gliz, Turin 2006

The choices for the 2006 Winter Games mascots were designs at their most elemental: Snow and ice. That was the inspiration for Neve, which means snow in Italian, and Gliz, which is short for “Ghiaccio,” or ice. The male and female characters had a snowball and an ice cube for their respective heads, and Gumby-like limbs that allowed them to be posed for any of the sports at the Winter Olympics.

In coming up with the aesthetic, Portuguese artist Pedro Albuquerque became the first Olympic mascot designer who was not native to the host country. A third mascot, Aster, a anthropomorphic snowflake, represented the 2006 Winter Paralympics.

Phevos and Athena, Athens 2004

When the games returned to the spiritual home of the Olympics 2,799 years after the first such games in Olympia, designer Spiros Gogos turned to ancient Greece for inspiration for the mascot.

So, the two characters shepherding in the 2004 Athens Games were shaped like ancient terracotta dolls that would have been in vogue in 776 BCE, the date of the first Olympics. The male and female mascots were dubbed Phevos, another name for Apollo, the god of the sun, and Athena, after the goddess of wisdom and the patron deity of Athens. Both were dressed in colorful tunics.

RELATED: See Team USA's Medal-Worthy Olympic Uniforms and Gear Ahead of the Summer Games

A seahorse named Proteas represented the Paralympics.

The designs met with spotty critical reaction initially but proved a big hit with their intended audience – children. “Our dolls combine a game with children and sports, as well as antiquity,” Gogos told the Greek outlet Kathimerini. “What could better connect the past and the new Games we want to organize?”

Powder, Coal, and Copper, Salt Lake City 2002

While at first blush, the three mascots of the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics seem like a simple collection of cartoon characters – a hare, a coyote, and a black bear – the choices worked on multiple levels.

Respectively named Powder, Copper, and Coal, that hare, coyote and bear represented the three main natural resources underpinning the Utah economy, with the smallest animal symbolizing the snow powder of the ski resort industry. Each respectively represented one of the three Latin words in the Olympic motto – Citius (faster), Altius (higher), Fortius (stronger). And finally, they were meant to represent the folklore of the Native American peoples of the region, which were heavily steeped in tales featuring those same animals.

Syd, Olly and Millie, Sydney 2000

Australia went big for the 2000 Olympics, producing three distinct official mascots, each an animal that was native to the Land Down Under. A concerted effort was made to avoid using kangaroos or koalas, the two animals most associated with the country by outsiders. The same probably held true for crocodiles and Great White sharks.

The results delivered by designer Matthew Hatton: Syd, a duck-billed platypus named after the host city of Sydney; Olly the kookaburra was nicknamed for the Olympics, and the anteater was dubbed Millie, in a nod to the new millennium.

“From a marketing perspective the trio of mascots for the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000 were useful,” said Cornwell. “Syd, a duck-billed platypus, Olly, a kookaburra, and Millie, an echidna represented Sydney and Australia in an understandable way and educated the world on the country’s wildlife. They symbolized water, air, and earth.

“At the time, some felt they had overly bold personalities, but they were true 'Aussies.'”

The Snowlets, Nagano 1998

During the campaign to bring the Winter Games to Nagano, Snople, a snow weasel native to the mountainous region in Japan where the Olympics would be held was used to drum up support. As it became apparent that the character wasn’t popular enough, the organizing committee pivoted and called for a replacement.

The result was four replacements: A collection of four baby snow owls, apparently to symbolize the four years between Games and the four seasons. Sukki, Nokki, Lekki and Tsukki, were collectively called the “Snowlets,” a combination of the English words, “snow” and “let’s” – an invitation for participation.

Izzy, Atlanta 1996

Izzy, the avatar of the 1996 Summer Games may have been the most tepidly received mascot in Olympic history. The Simpsons creator Matt Groening, for example, dismissed the blue character with stars in its eyes and lightning for eyebrows as a, “bad marriage of the Pillsbury Doughboy and the ugliest California Raisin,” a reference to a Claymation advertising campaign of the era.

Still, the name was an improvement on its original moniker, Whatizit.

RELATED: Meet the Olympic Couples Cheering Each Other to the Finish Line

Given a mandate to avoid any connection to some of Atlanta’s uncomfortable history, including slavery, designer John Ryan opted for a symbol tapping into the rise of information technology. This was the height of the early Internet era, after all.

“The basic job was to design something that would appeal to children and broadly on a world stage,” Ryan told Atlanta magazine in 2016. “There was a mention of trying to acknowledge regional flair. For me that meant they were going to get designs that were pecans and peanuts and pooches. So I fell back to classic design technique, seeing things from the perspective of an alien who had just landed here.”

Håkon and Kristin, Lillehammer 1994

The first human mascots for the Olympics arrived in 1994; for the first Games of the IOC’s new schedule of alternating between the Winter and Summer Games. Their names Hakon and Kristen were in homage to real-life figures from Norwegian history: Håkon IV Håkonson, a king who ruled in the 13th Century, and Princess Kristin, his aunt.

The pair were depicted as two blonde children in Viking clothes, allowing multiple child actors to play Hakon and Kristen for publicity purposes. The characters remained popular in the country long after the Lillehammer games ended because of their symbolic ties to Norse culture.

A troll with an amputated leg named Sondre was later introduced as the representative of the Paralympics.

Cobi, Barcelona 1992

Artist Javier Mariscal’s winning design for the 1992 Barcelona Games was a cubist anthropomorphic cartoon dog that became one of the most popular mascots in Olympic history. Cobi, named after the acronym for the Olympic organizing committee for the Barcelona (COOB), is a Catalan Pyrenees sheepdog, a popular breed in the country.

"Ideally, you should always try to draw your design as clean and fast as possible. A mascot has to be iconic, have a unique identity so that you see it and in a second you say 'Oh look, that is the Barcelona 92 mascot'," Mariscal told Domesika.

For the 30th anniversary of the Barcelona Games, Mariscal released an updated image of an older, bearded Cobi with glasses and a mobile phone.

Magique, Albertville 1992

In a departure from the typical mascot design of cutesy animals, the 1992 Winter Games in Albertville, France would feature an imp shaped like a cube within a star. Magique, meaning French for magic, was decked in the colors of the national flag. The character was meant to be the embodiment of imagination.

“There was a desire to step away from traditions like animals or things for kids,” designer Philippe Mairesse told Olympics.com in 2022. “The whole visual identity [of Albertville 1992] was very abstract, graphic and based on atmosphere and ambiance.”

The Albertville mascot nearly had a completely different look. The original choice was a mountain goat before organizers changed their mind.

Hodori, Seoul 1988

Hodori, the name for the mascot for the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul, is a combination of the Korean words for tiger (“Ho”) and boy (“Dori”). An appropriate choice of animal given the tiger’s place in Korean folklore as guardians. Besides, designer Kim Hyun really liked tigers.

“Just as the United States has the bald eagle, Russia the bear and China the panda,” Kim told Korea JoongAng Daily 30 years later, “an animal can become a national symbol and a huge asset to the nation.”

The artist embellished the mascot design to incorporate more cultural touchstones, including a traditional Korean hat called a sangmo that included a ribbon shaped in an “s” to honor the host city. The look was completed with a necklace featuring the Olympic rings.

RELATED: Everything to Know About the 2024 Paris Olympic Village

There was also a female version of the tiger mascot designed for the games dubbed Hosuni, with the second half of the name being Korean for girl.

Hidy and Howdy, Calgary 1988

The mascots designed by Sheila Scott for the 1988 Winter Games in Calgary would be a milestone in Olympic history: the first to feature male and female versions. The polar bears were dubbed Hidy, riffing off the greeting, “Hi,” and “Howdy,” short for “how do you do,” in a nod to the Western Canadian penchant for politeness.

They were dressed in Western-style hats and outfits to symbolize the province that’s famous for the annual Calgary Stampede, the world’s largest outdoor rodeo.

Sam, Los Angeles 1984

One of the early ideas under consideration for the mascot of the 1984 Los Angeles Games was a bear, the official state animal of California, but it was tossed because it was too close to Misha the Bear, the popular Russian mascot of the previous Moscow Games. The team of 30 designers led by Disney publicity veteran Bob Moore settled on a national symbol – the bald eagle.

The worry was that the natural look of the bird would be too fierce for children, a key component of the marketing and corporate sponsorships on which organizers were banking. So, Moore opted for a more cartoonish look, bearing a slight resemblance to the animated parrot Jose Carioca from the 1944 Disney film, “The Three Caballeros.”

“Since the eagle would have to be shown as a competitor in the various athletic events, the wings were drawn to function as “arms” and the feathers as “fingers,” according to the official report of the 1984 Olympics.

The successful marketing campaign is one reason that the 1984 Games became the first Olympics since 1932 to actually make a profit ($225 million) for the host country.

Vučko, Sarajevo 1984

Yugoslav newspaper readers voted on Vučko the Wolf over five other finalists – a chipmunk, a mountain goat, a porcupine, a lamb, and a snowball – for the mascot of the Sarajevo Games. The winning design, by Slovenian illustrator Joze Trobec, honored the wolves that roamed through both the forests of the Alps and Yugoslavian folklore.

But this cartoonish version was embellished with a “Sarajevooo” howl that also honored the host city of the 1984 Winter Games.

Misha, Moscow 1980

After a public poll cemented the choice of a bear for the mascot of the coming 1980 Summer Games in Moscow, children book illustrator Victor Andreyevich produced the winning design that beat out some 60 other entries. Misha the Bear, or Mikhail Potapych Toptygin as the bear was officially named, had a welcoming smile, an effort to ease some of the Cold War era tensions between the Soviet Union and the West … at least for the duration of the Summer Games.

Misha is still a beloved symbol in Russia nearly 50 years later.

There was also a second mascot of the 1980 Games -- Vigri, a baby seal in a bathing cap representing the yacht races held in the Baltic Sea – that has been less well-remembered.

Roni, Lake Placid 1980

What better animal to represent the 1980 Winter Games in Lake Placid than the racoon, a critter well-known to residents of the Adirondack mountains in upstate New York. In fact, a living racoon mascot was originally chosen to represent the Games. When the racoon died shortly before the start of the game, however, it was replaced with an illustrated version courtesy of artist Don Moss.

RELATED: Who's on Team USA? Here's a List of the Athletes Qualified for the 2024 Paris Olympics

The name Roni, chosen by local school children, means “racoon” in Iroquoian, the indigenous nation that inhabited the region. There were 13 designs of Roni performing different winter sports as part of a marketing push to celebrate the Games.

Amik, Montreal 1976

The symbol of a beaver was a natural choice for the mascot of the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal given its place in Canadian ecology and the role of the pelt trade in Canadian history. In fact, the beaver would be minted as the official animal of Canada the year before the Games.

Amik, which means beaver in Algonquin, a language spoken by many indigenous people in the country, was designed by Guy St. Arnaud, Yvon Laroche and Pierre-Yves Pelletier of the design team for the Montreal Olympics. The mascot’s look was finished with a colorful sash featuring the Montreal Games logo, patterned after the ribbon used for winner medals.

Schneemandl, Innsbruck 1976

Appropriately enough, Schneemandl means “snowman” in German, as that’s exactly what the mascot for the 1976 Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria, is supposed to be. Designed by Walter Potsch, this snowman incorporated a number of touches native to the host country, including his traditional red Tyrolean hat.

The design proved a big marketing success, in part because of the ubiquitous appearance of performers in Schneemandl mascot costumes at the Games.

Waldi, Munich 1972

The first official Olympic mascot debuted in Munich in time for the 1972 Summer Games, a dachshund inspired by a real dog owned by one of the organizers.

Graphic artist Elena Winschermann, a member of the team assisting noted artist Otl Aicher, came up with a design that ringed the mascot’s body with the official colors of three of the five Olympic rings – blue, yellow and green. Red and black, the remaining colors, were purposely left off to avoid associations with the Nazi flag.

Shuss, Grenoble 1968

Designer Aline Lafargue reportedly only had one night to create a character that would embody the games held at the town in the French alps. The result was a skier with a red head, blue lightning-bolt body, and one ski named, “Shuss,” based on the French verb for skiing downhill.

Though not the first official mascot, Shuss was a ubiquitous presence at the Games in the form of keychains and other merchandise.

Smoky, Los Angles 1932

Long before the recognition of official mascots at the Olympics, athletes at the 1932 Summer Games anointed a black Scottish terrier as a mascot. Smoky the dog was born the day construction began on the athlete’s village and continued to roam the area during the Games, according to a UPI report from the era.

And the next generation of Olympic mascots is already here….

Tina & Milo, Milano Cortina 2026

The next Winter Olympics are almost two years away, but the pair of adorable stoats – small mammals that are related to weasels and ferrets and native to much of Europe – representing the twin Italian host cities of Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo are already here. Siblings Tina and Milo, named in a nod to the cities, are the result of a nationwide design contest for primary and secondary school across the country that generated more than 1,600 entries, according to organizers. Tina represents the Winter Games, and Milo is the avatar of the Paralympics.